My name is Federico Guzmán. I am from Seville, a visual artist and researcher. Along with my own studio work, I participate in collective projects, addressing learning across cultures and questioning the egocentric perspective. For me, the collaborative process is a path to self-knowledge that moves from the consciousness of separateness to the consciousness of unity.

Assalam: Peace

There is an idea in ancient art that the function of the artist is not simply to please, but to present “something that must be known” in such a way that it pleases or delights when seen or heard, and to express it in such a way that it is convincing. It must be made clear that it is not the artist, but the human being, who has both the right and the duty to choose the subject; that the artist is not licensed to say something that in itself does not deserve to be said, no matter how eloquently he says it; And that only through his wisdom as a human being can the artist know what deserves to be said or done. Art is a kind of knowledge with which we know how to do our work, but it does not tell us what we need to say, and therefore what we should do.

In the Sahrawi culture, the encounter is preceded by the long and attentive Bedouin greeting that Sahrawi men and women profess to each other daily in the desert. It constitutes a true recognition of the humanity of the person in front of you and embodies a deep knowledge of life. In the countries of the north, knowledge of the “other” comes first, and then its recognition. Conversely, in the countries of the south, recognition comes first and then knowledge. There is a human presence, a reflective identity that does not need knowledge to be able to say that we belong to a single humanity. Based on this logic, intercultural dialogue is possible.

The first time I traveled to Western Sahara, I hardly knew its history. I had heard about the former Spanish colony, the only people in Africa that had never gained their independence, and about the shameful historical circumstances in which the Spanish government abandoned the Sahrawis to their fate in the face of the Moroccan military invasion in 1975. But when I arrived at the refugee camps in Tindouf, I was struck by the dimension of the human tragedy and the injustice experienced by the Sahrawi people, an Arab and Muslim culture with a nomadic tradition, of noble and hospitable people. I was moved by the dignity with which the Sahrawis endure the harsh conditions of exile in the desert, the wisdom of the elders, the courage of the women, the smiles of the children, the patience and determination of an entire people and even their sense of humor. From the first day I felt at ease among my friends, and I have not stopped learning from them.

Saleh Brahim

Learning across cultures places us in an anthropological perspective. In his book The Aesthetic Experience, An Anthropoligist Looks at the Visual Arts, Jacques Maquet states: "Our point is that human commonality must be as meticulously considered as diversity. All human beings have much in common: similar mental and physical equipment, the same life cycle, the same needs, the same fears. Common human nature and the common human situation are also determinants of behaviour. It is hoped that anthropology will at least recognise that beyond the cultural level, there is also a pan-human level."

Sahrawi Art School. Camp Boujdour, Algeria

The “human as such” cannot be expressed or perceived because it cannot exist free of cultural determinations. In visual experience, the human and the cultural are one. Any activity, behaviour or artefact includes a singular component. (…) We can go a step further and understand that the unity of experience is located in the individual observer.

Traditional sand game

Interculturality does not mean cultural relativism (one culture is worth as much as another), nor fragmentation of human nature. Every culture is human culture, even if it can degenerate. To put it more philosophically, there are human invariants, but there are no cultural universals. Their relationship is transcendental: the human invariant is perceived only within a certain cultural universal. All men eat and sleep, but the meaning of eating and sleeping is not the same in different cultures. A profound knowledge is revealed in the beautiful verse of the Koran: “I made you peoples and nations so that you might learn to live together.”

Sahrawi and Spanish artists at the Sahrawi Art School

There is certainly no global perspective. Every perspective is limited, but there is always the possibility of an exchange and an expansion of perspectives, and intercultural dialogue aims precisely at this non-dual intuition: to guarantee that cultural diversity is not synonymous with violence or conflict, and that unity is not suppression of differences or totalitarian monoculture.

The Arts and the Human Rights course between Adelphi University NY and the Abidin Kaid Saleh Film School camp Boujdour, 2013.

As artists from different cultures, we not only share a dialogue between individuals rooted in their substratum and personal history, but we open ourselves to an osmosis between two visions of reality, between two worlds represented by human beings who carry with them the unconscious heritage of the history of their respective cultures: Spaniards and Saharawis, East and West, Europeans and Africans, men and women, religious and secular, travelers and nomads, refugees and expatriates.

Caravan of the Culture Festival of the Sahrawi Republic, 2015.

Working together is, in itself, an act of resistance: leaving the known and crossing differences of age, education, worldviews and experiences. We must patiently adapt to the other, harmonize cultural and linguistic differences, overcome uncertainties and resolve disagreements. It also shows how much colonialism still survives in our unconscious… and how much more exists in our society of malaise. In the opposite situation, where a Sahrawi artist came to work in Europe, the difficulties of bureaucracy and visas would become even more evident.

Burying the ego of the individualist author in the sand of the Sahrawi camps, the artists open themselves to mutual listening and the conversation springs up from below, weaving into an ethical and poetic work, radically collaborative.

Mohamed Baecha

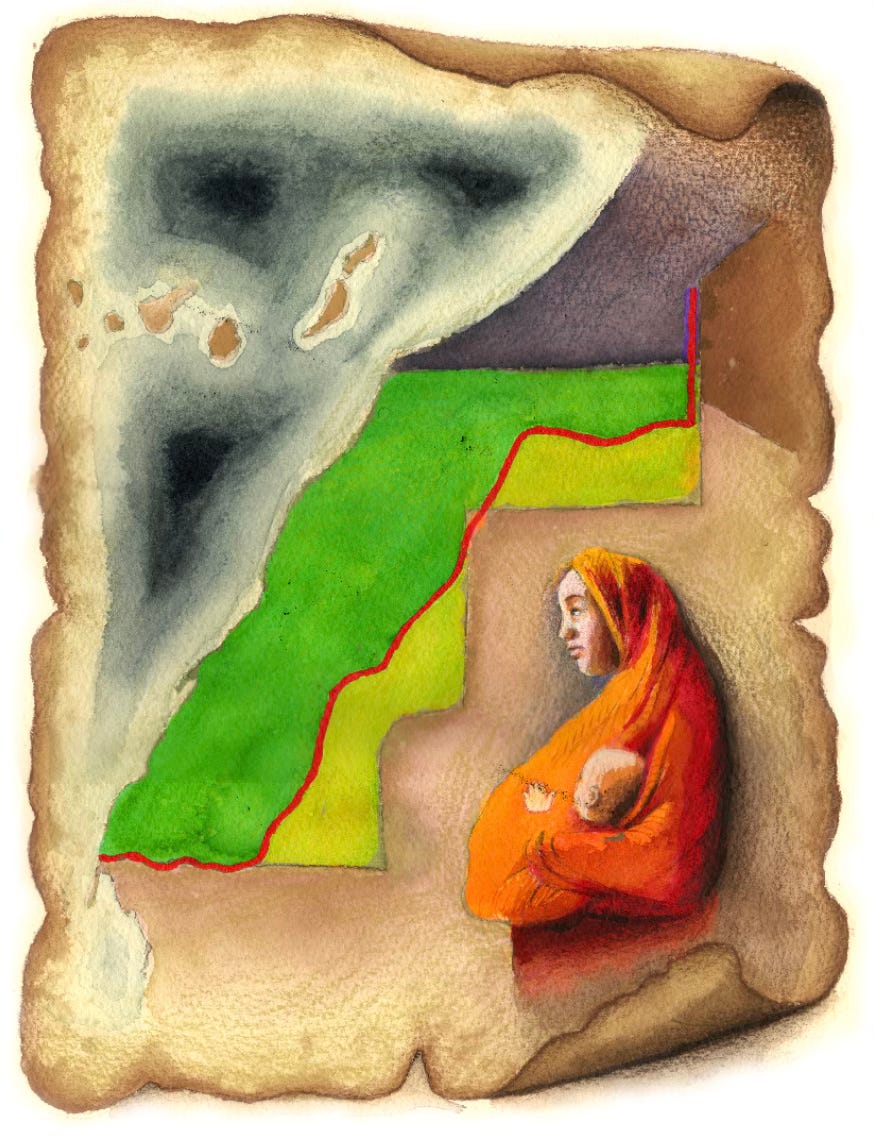

The experiences lived in exile and those imagined in their occupied land are juxtaposed. They speak of the Moroccan Wall of Shame, which separates the territory and families of Western Sahara, of the mirror image, of the gaze of the “other”, of the complementarity of masculine and feminine energies, of the deep identity of culture and nature. Paths are opened on the border, following a sinuous and discontinuous narrative that takes us from the city to the refuge, from the sand to the river, from the industrial outskirts of our cities to the adobe houses, from shadow to light and from wakefulness to sleep. A vision that enters and leaves the mirage of separation in an endless blink.

Maddi Ahmed

Sahrawi artists paint political, epic and everyday pictures, their poems are manifestos of uncertainty, protest and hope, their music is reivindicative, combative and inspiring and their cinema is committed to the revolutionary effort of their land. Their art is the intifada of a new transformative avant-garde. We observe in them an urgency, a crudeness and an immediacy so powerful that they can sometimes destabilize our sophisticated Western gaze.

Justice Camp collective painting

Sahrawi artists do not protest for copyrights, they do not make their work for catalogues, nor selfies for social media. Although we can make postmodern, deconstructive or post-structuralist analyses of their work, it is above all an indispensable insurgent, deautomatizing, decolonial, collective and healing tool for psycho-aesthetic, communicational and socio-expressive development.

Um Draiga. Mohamed Moulud Yeslem, Tifariti 2010.

It is the cry of rebellion of an entire people, in a non-violent struggle for their dignity as people, for their land, their roots and their freedom. Many of them had not thought of being artists, but instead of grabbing a rifle, they have taken a brush with paint, and have seen that they can, instead of shedding blood, smear the world with colors, messages and symbols. Every Saharawi is an artist when he discovers within himself a light that allows him to transcend his condition of exile, and recognize himself as a creator, capable of transforming reality, giving meaning to his life by drawing the collective destiny.

ARTifariti 2009.

They know that their effort is a daily and permanent process. Conflict is not something that we will overcome forever, but rather part of the continuous evolution of existence. Access to goods must be conquered every day, the same in the Sahara as in all our societies.

Nejma Saharauia. Rubén Polanco 2010.

An Egyptian activist in Tahrir Square left a door open to hope with his words. “If we are optimistic, we do not have to wait for a utopian future. The future is an infinite succession of present moments. And living now as we think human beings should live, facing everything, is already a wonderful victory in itself.”

Esseniya Ahmed Baba

Ultimately, this reflection challenges us as humanity. We must never forget that identity struggles have a strategic character, in the sense that they seek emancipation not only as peoples but in a human and collective horizon that people like the Algerian revolutionary Frantz Fanon considered the horizon of our struggles.

Mohamed Sleyman Labat

This horizon is what opens the way to a new condition, where identity no longer matters, where difference no longer counts, because we have all become simply human beings, children of Mother Earth. Our identity is a beautiful relative circumstance, which celebrates the diversity of life as an inseparable part of the universe.

Tessawar assalam: Imagine peace

Shared experiences take us beyond the borders that separate us, celebrating the unity of art = life. A meeting of profound self-discovery, of each and every one, in a primordial Self. This is a path to “change the dream of the earth”, and place ourselves once and for all in another paradigm of consciousness: a transcendent intuition that is inevitably accompanied by the responsibility of something higher. Higher than my family, my country, my tribe, my team, my success. A collective responsibility for all humanity and the Earth. So that we can resolve conflicts not by resorting to the use of force and violence, but through closeness and compassion.

Nomadic Memories, Pain and Resistance in Western Sahara. (Download at https://publicaciones.hegoa.ehu.eus/uploads/pdfs/247/memorias_nomadas.pdf?1488539803)

We were fortunate enough to collaborate on the book Nomadic Memories, where particularly significant cases of violations of human rights were treated in a close, intimate, subjective way accompanied by our drawings.

Federico Guzmán

From the exodus to the desert, to the bombing of the civilian population in 1976. From the pillage of camels and tents, to forced disappearances and clandestine detention centres. From torture and arbitrary detentions, to the time spent resisting oblivion.

Destruction of Gdeim Izik camp

Alongside all these human rights violations there are hidden stories that have a name, a face and a heartbeat. In these pages, Sahrawi women and men give lessons of wisdom and courage.

Stories of shelter and patience, woven with drawings that embrace them, caress them or shout them out. Some drawings were made while taking the testimonies; others were born from the dialogue with the voices and reflections of the people. This dialogue is also an invitation to the people who share it now. To you.

Taking testimonies at Brahim Dahan’s house, El Aaiún.

We are learning to transcend field research in the scientific and objective way of anthropology to make the collection of data situated, dialogical and intersubjective, an exchange of gifts (“data”, from the Latin datum: gifts) of an experiential nature. By recognizing that objectivity is an illusion, we become a filter and magnifying glass of the story. In this way, many things can be communicated that are untranslatable, things that can only be said with an intimate story, through associations and metaphors in the close manner of poetry.

Sukeina Yiddahlu by Alonso Gil

This way of narrating is based on drawings, colours and strokes, with atmospheres that bring us to the place of the story in an evocative way. Drawing has a power that no other form of testimony has. Its images evoke reality in a slower, sometimes silent way, and work in the mind of the reader who can choose their pace.

This process is based on the recognition that the deepest thoughts and feelings of the human being, coming from the unconscious, are better expressed in images than in words and that each individual, with or without training in art, has the latent capacity to project their own conflicts in a visual way.

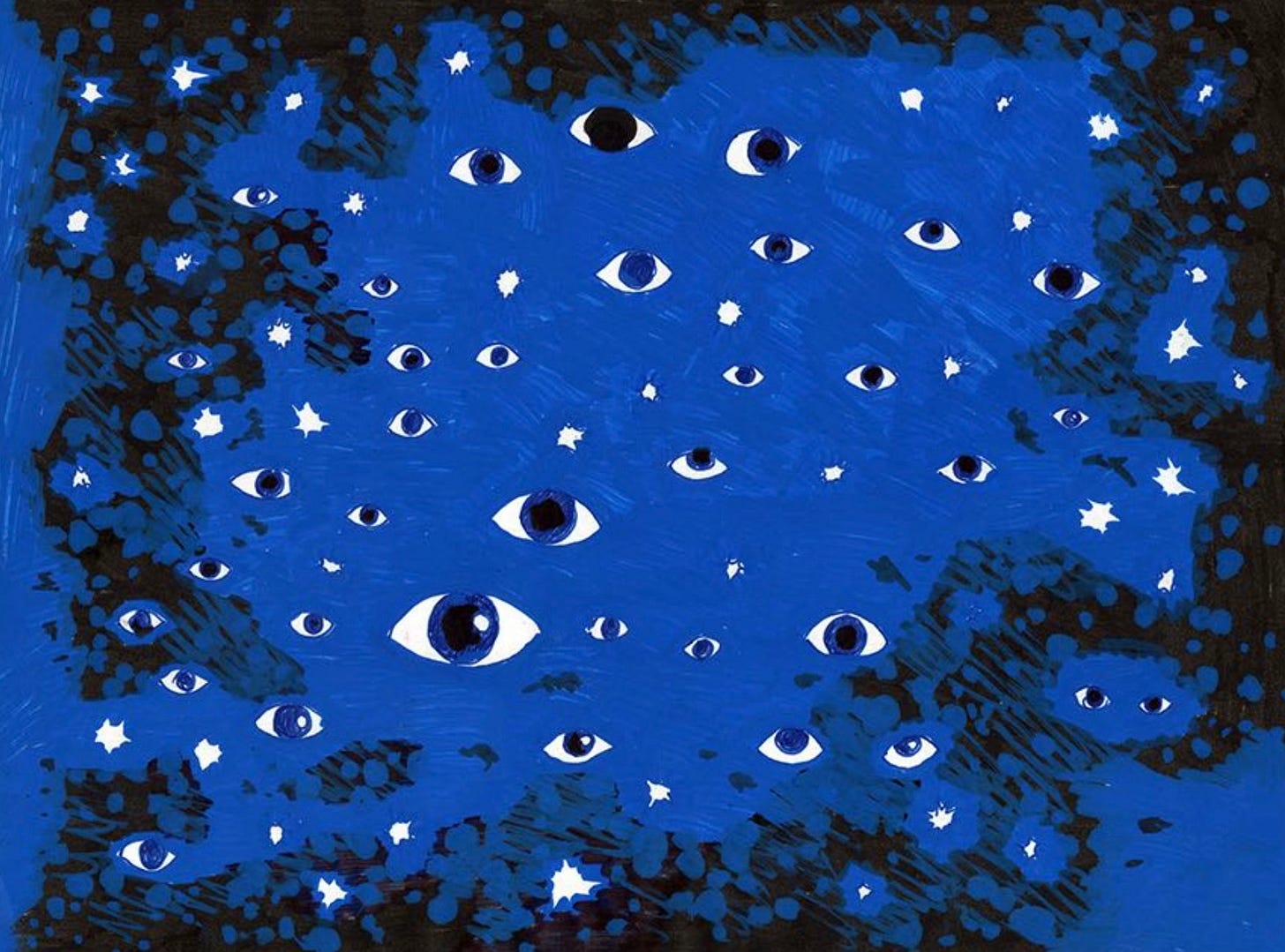

This journey through indignation was a slap in the face of conscience that opened our eyes to the nightmare in which the Saharawis wake up every day. El Aaiún, Al-Ayyün, in Arabic “the eyes” or springs, is the name of this city founded by Spaniards next to water sources that already gave name to the area. Transparent and true eyes that Morocco wants to blind by beating. Eyes of the world that must be opened to the reality of the suffering of this people.

Our friend and host Brahim is the first to share his experiences with us, clarifying from the beginning: “I hate to tell the details, it hurts me. But people must know.” Thus we meet with Elgalia, Aminetu, Sukeina and numerous victims of repression. Elghalia describes to me the shape of the hooks in the slaughterhouse where she was hung for days. And she also explains how she communicated with fellow prisoners by writing on a plastic plate with the thread of her tattered melhfa.

Said Hadad, 29 years old, disabled, humiliated, insulted and beaten more than a dozen times by the Moroccan occupation forces.

We go through our notebooks and start talking about the work. We talk about how these drawings tell stories, but in a non-literal way. Our drawings are not documentary but rather subjective, they are recreations rather than illustrations. In a sense, they can be understood on a transactive rather than a communicative level. They are drawings that touch us, but do not necessarily communicate the “secret” of a personal experience that is perhaps indescribable.

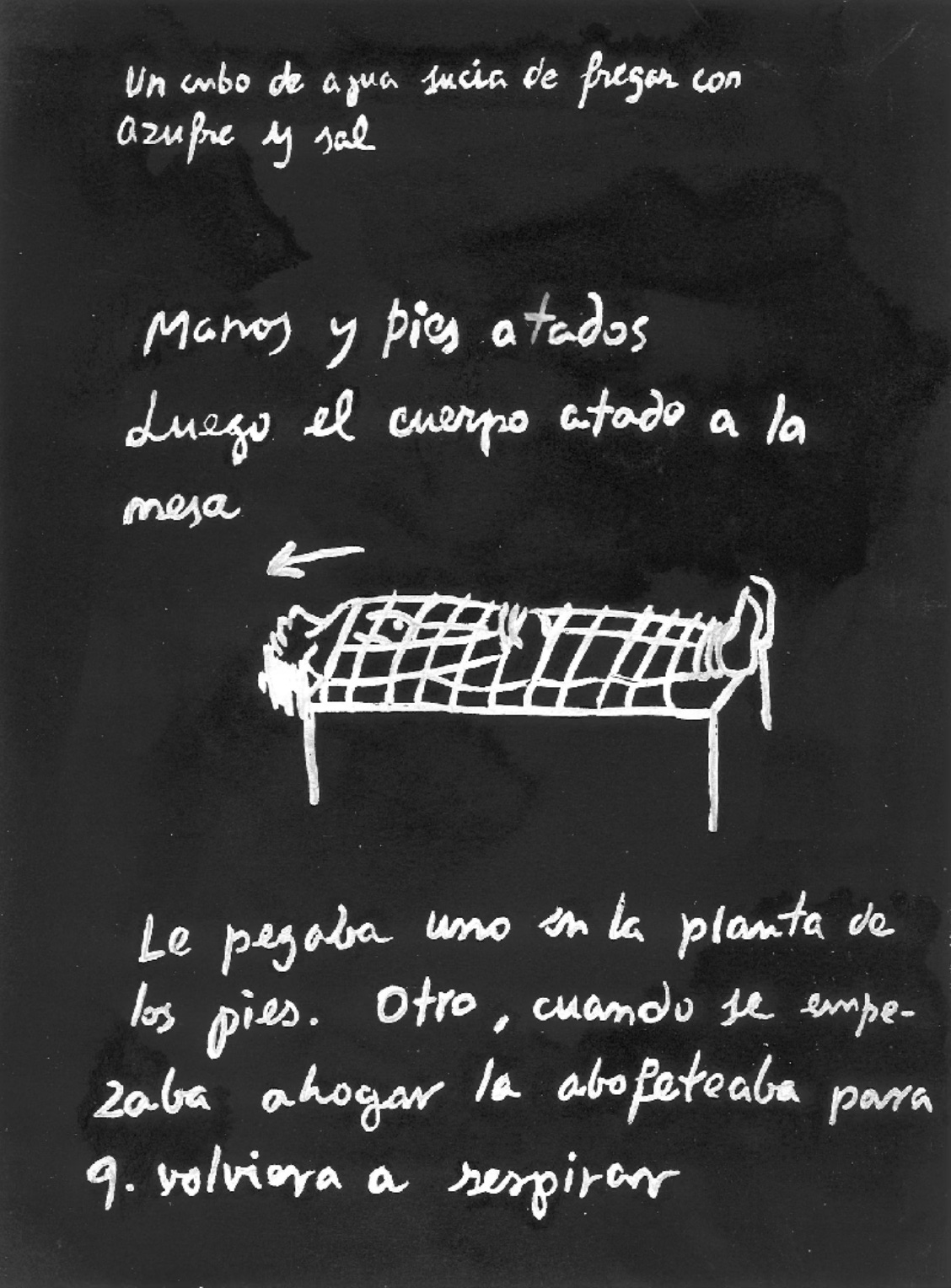

The banality of evil: the names of torture are “roast chicken” (hanging from a bar), “the airplane”, “the crane”, “the plank”…

As Elgalia Djimi explained it: the naked body tied to a table. A guard hit her on the soles of her feet. A bucket of dirty water from mopping the floor with sulfur and salt was thrown over her face. When she began to choke, another guard slapped her to make her breathe again.

The drawings invite empathy between the viewer and the primary experience of trauma in a reflective, subjective, open and critical way. The drawings evade any totalisation or objectivity. They are fragments of a montage where the story is a discontinuous continuity, sometimes straight as the horizon of the desert, sometimes sinuous as the sand tracks of memory.

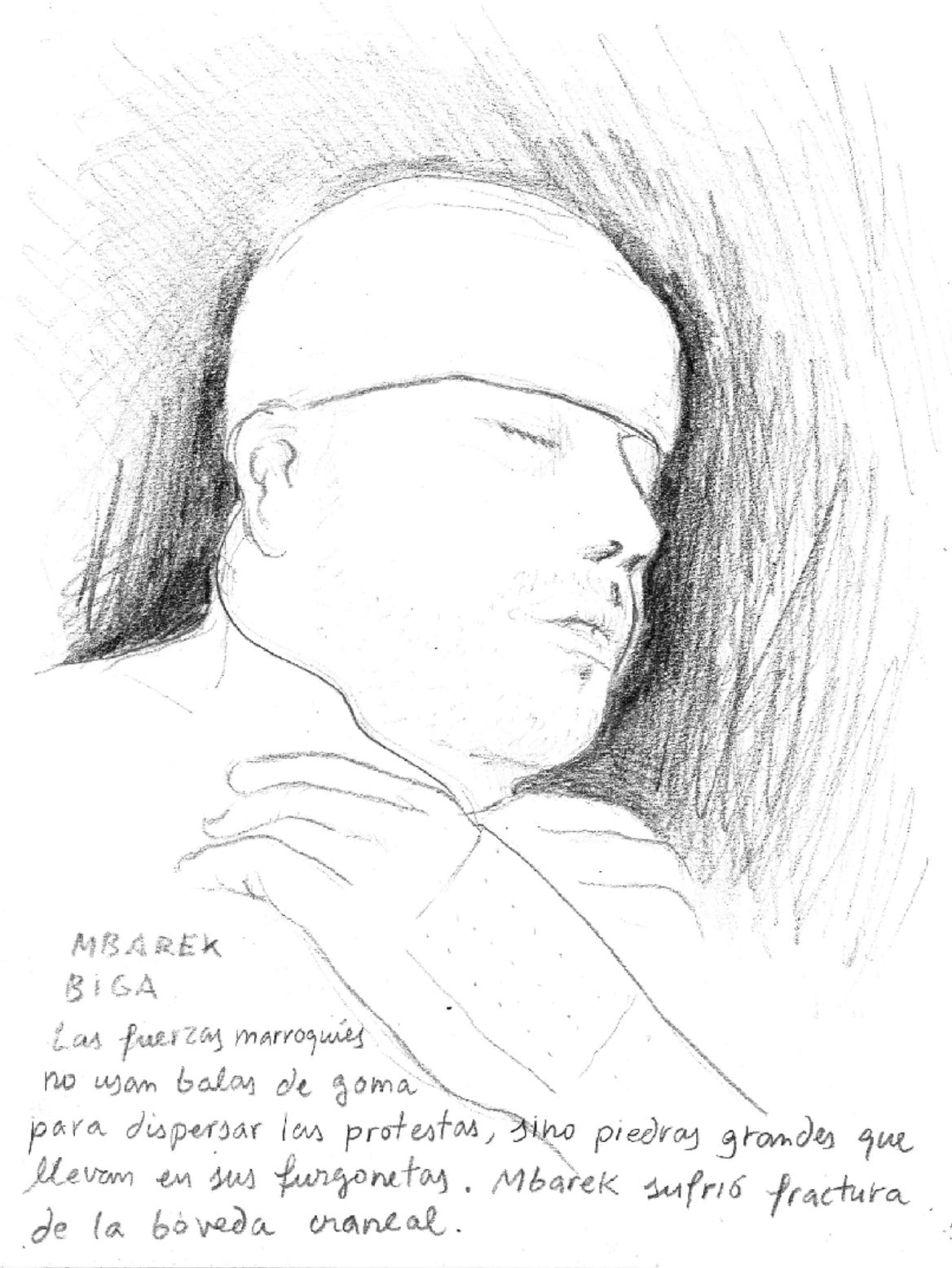

Mbarek Biga. The Moroccan forces do not use rubber bullets to disperse protests, but large stones that they collect from the beach and carry in their vans. Mbarek suffered a fractured cranial vault and has been depressed ever since.

Sidi Mohamed Dadach. Sentenced to death. After Mandela, he is considered the African political prisoner who has spent the longest time in prison. He has received the RAFTO award for human rights.

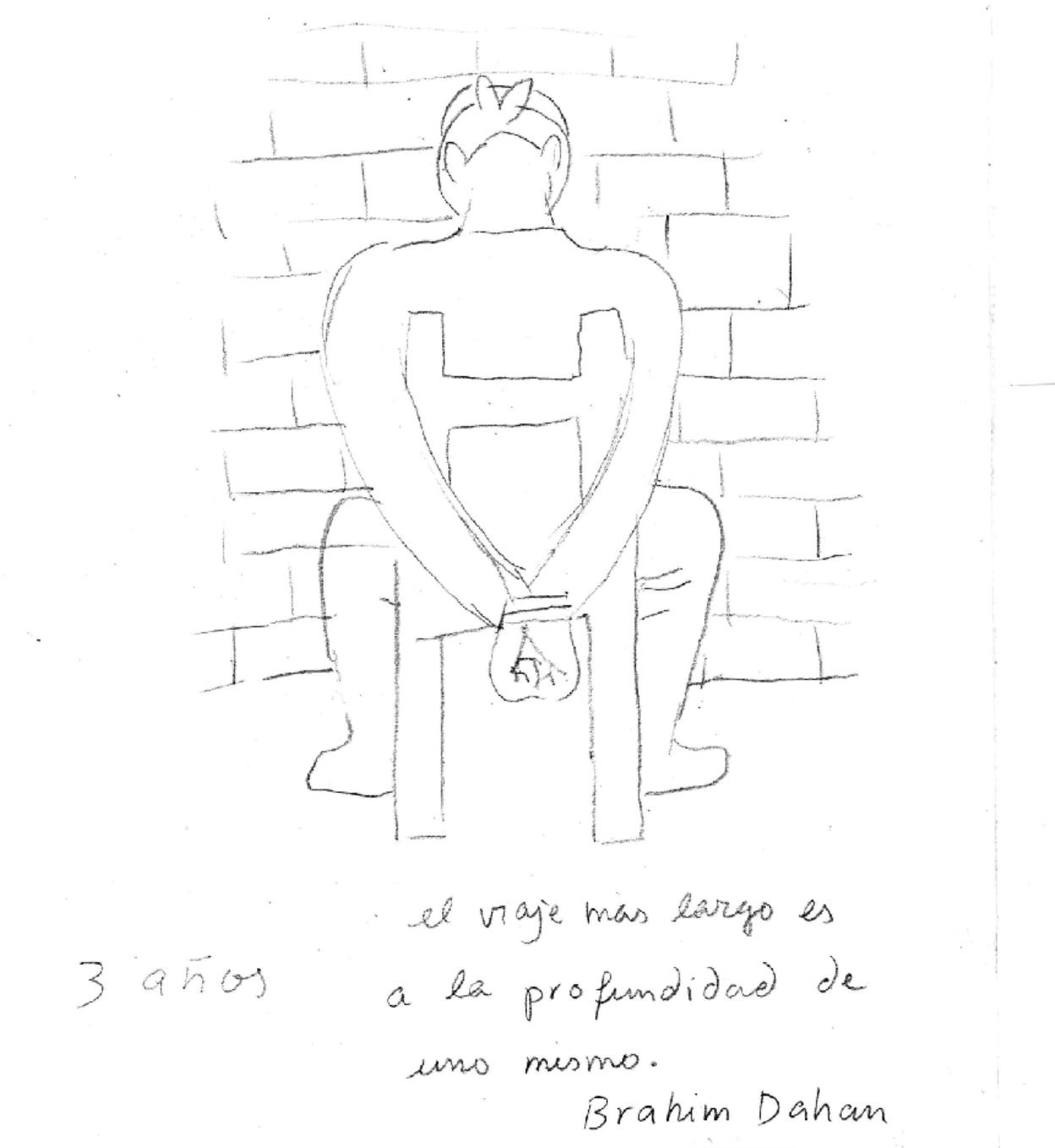

Brahim Dahan. Three years tied to a chair with a blindfold on. He told us that “the longest journey is to the depth of oneself.”

Elgarhi Nayem Foidal. Killed at the age of 14 in the Gdeim Izik protest camp. The vehicle he was travelling in with his family was shot at when he ran a police checkpoint. How much blood must be spilled before the international community opens its eyes? How many Elgarhi Nayem Foidals do we have to bury before the world softens its heart?

Many of the fractures are on the left side of the body. Because they are engaged from the front and hit with the right.

Trauma is the emotional response a person experiences after being exposed to life-threatening events. Through art, you are ultimately taking care of yourself. You see yourself as you are at this moment. You are dealing with despair, sadness, emotional trauma and you are trying to put it into perspective

Brahim Dahan, a Sahrawi human rights activist and president of the Sahrawi Association of Victims of Serious Human Rights Violations Committed by the Moroccan State, was arrested at a protest where he recalls “the police beatings falling on him like rain.”

In 1987, Aminetu Haidar participated in a non-violent demonstration against the Moroccan administration of Western Sahara. Along with many other attendees, she was subjected to enforced disappearance by the Moroccan authorities and held without trial until 1991, when she was released. According to Kerry Kennedy of the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights, Haidar was “gagged, deprived of food, sleep, subjected to electric shocks, brutally beaten and worse” during her imprisonment.

These drawings speak of memory and allude to the proverbial memory of the camel, which, once it has drunk from a fountain, always knows how to remember the way back. The camel is also capable of remembering those people who have wronged it at a given moment.

The situated practice of art as non-violent action can be compared to that “correct action” or inspired action whose prerequisite is awareness. An awareness that, according to wisdom philosophy, means fighting for peace from peace, acting in the face of conflict from happiness and from the acceptance of what is, without resigning ourselves to oppression or injustice; understanding that silence is the background of the cry; that inner stillness and diligent action are compatible, inner contentment and denunciation; serenity and energetic anger punctually in the face of injustice – “an anger that arises without anger.”

This means understanding that art and activism that passionately fight for what must be changed, can at the same time and at every moment be an end in themselves, a contemplative act and an offering, illuminated by the vision of the Real. As Hans Georg Gadamer defines it: “a victory over the past, an art where everything becomes present.”

After eighteen years of continuous work in the place, we have lived a unique opportunity to learn by unlearning. After five centuries of teaching, the north no longer has anything to teach. The time has come to learn from the knowledge of the south. And to do this we need to unlearn all the knowledge we have acquired in universities, from our culture. Unlearn things in order to learn other things. Together with the artists we have understood that opening up to the “other” means abandoning all distinctions between me and you, to recognize by knowing what we are: one humanity, resisting, creating and pushing together.